HKCO

Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra Environmental, Social and Governance Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for Life Orchestra Members Council Advisors & Artistic Advisors Council Members Management Team Vacancy Contact Us (Tel: 3185 1600)

Concerts

Education

The HKCO Orchestral Academy Hong Kong Youth Zheng Ensemble Hong Kong Young Chinese Orchestra Music Courses Chinese Music Conducting 賽馬會中國音樂教育及推廣計劃 Chinese Music Talent Training Scheme HKJC Chinese Music 360 The International Drum Graded Exam

Instrument R&D

Eco-Huqins Chinese Instruments Standard Orchestra Instrument Range Chart and Page Format of the Full Score Configuration of the Orchestra

45th Orchestral Season

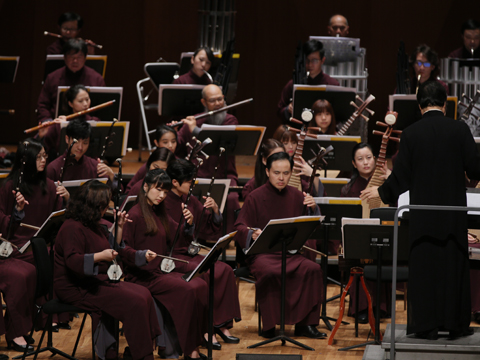

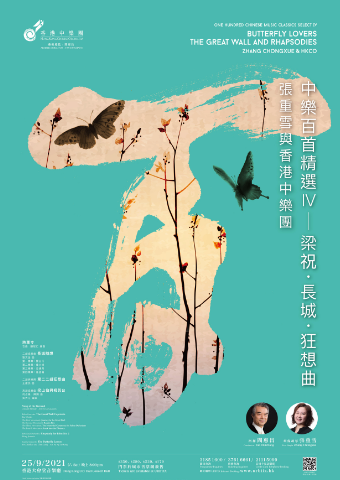

One Hundred Chinese Music Classics Select IV -

Butterfly Lovers, The Great Wall and Rhapsodies - Zhang Chongxue & HKCO

Erhu Concerto The Great Wall Capriccio Liu Wenjin

First Movement: Journey to the Great Wall

Second Movement: Beacon Fire

Third Movement: The Memorial Ceremony for Fallen Defenders

Fourth Movement: Look into the Distance

Erhu and Orchestra Rhapsody for Erhu No. 2 Wang Jianmin

Gaohu Concerto The Butterfly Lovers He Zhanhao and Chen Gang Arr. by Ng Tai-kong

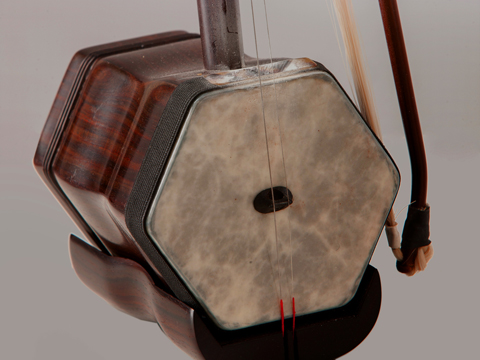

The Road to Contemporary Music for the Huqin

Christopher Pak

The last two decades of the twentieth century was a period when transcriptions of violin show pieces for the huqin became the focus of many musicians. Virtuosic techniques exhibited in transcriptions of violin works like Sunshine over Tashkurgan by Chen Gang, Carmen Fantasy by Pablo de Sarasate, and Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso by Camille Saint-Saëns were regarded by many as the ultimate yardsticks to measure the standard of any huqin players.

Transcription as a means to expend the repertoire for a particular instrument is not uncommon, particularly for instruments with limited repertoire. Carefully transcribed and interpreted, these works still have their own artistic merits.

Understandably there are alternative views regarding this practice, arguing that transcriptions have done little to enrich the artistic quality of music for the huqin and should not be adopted as regular practice. The first reason to support this argument is that transcriptions are based on works composed for other instruments and cannot fully explore the idiomatic features of the huqin. The second reason is related to the act of transcription itself. Technically demanding passages in the original work are quite often being compromised in the transcriptions in order to meet the idiomatic features of the new instrument. As a result, the transcribed work may lose some of its virtuosic merit.

In recent decades, repertoire for the huqin has experienced rapid expansion. For well-established artists, those dazzling virtuosic transcriptions are not necessarily the only crown jewels. Today people can enjoy these pieces from a more objective perspective. While we are accepting that these pieces have made important contributions to consolidate the performance techniques of the huqin, their value to enrich the artistic quality of music for the huqin is now being reexamined with reservation.

These changes are not because of audience losing their interest in these pieces. The main reason is that music composed for the huqin has changed a lot since the 1990s. Works with more ambitious scale have replaced short character pieces as mainstream, leading to new sophistications in formal structure, artistic aspirations and technical demands typical of new works for the huqin. As virtuosic music, these recent works are more idiomatic, and exhibit a musical style with national character. The series of “Rhapsodies for Erhu” composed by Wang Jianmin are some of the most notable examples of this new trend. These pieces have incorporated musical elements borrowed from various regional music genres and music of the ethnic minorities. Virtuosic demands in these pieces are also more idiomatic. Recent works for the huqin, including works that are inspired by popular music, generally adopt Wang’s approach that combines vivid melodic lines with virtuosic character.

Retrospectively speaking, the works of two composers have paved the way for these new trends. The first composer is Liu Wenjin, whose Northern Henan Ballade and Three Gorges Dam Capriccio, composed in 1958 and 1960 respectively, have brought the music for erhu to a new height. Both pieces are also among the very few compositions remaining in the standard repertoire that depict the grandiose irrigation projects during the Great Leap Forward movement. The artistic merits of these two pieces have clearly overshadowed their political implications. Liu’s erhu concerto Great Wall Caprice, composed in 1978, remains a landmark in representing the development of Chinese instrumental music of the 1980s. As a reflection of the history of the Chinese people, the subject of concerto also foresees that the country is ready to move forward after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The attempt for the composer to consolidate his own reflection of national history as subject in the music has inspired numerous works thereafter.

The second composer is He Zhanhao. His Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto, a collaborative work with Chen Gang, is regarded as a classic to showcase the perfect combination of Chinese national music elements with large scale music genres in Western classical music. The concerto has been transcribed for numerous instruments, including those for erhu and zheng by He Zhanhao himself, though the transcription for gaohu has remained the most popular version for most audience. In fact, He Zhanhao has also composed four other erhu concertos, namely Fantasia of the Girl Named Mo Chou, Love in Troubled Times, Farewell Grief, and The Story of Comrade Yang. Only Kuan Nai-chung has composed comparable number of concertos for erhu. Moreover, He Zhanhao’s skillful incorporation of elements borrowed from traditional operatic music and narrative scheme in large formal structure like concerto has inspired generations of composers.

Since Liu Tianhua completed his first erhu piece Sigh of Ailment in 1918, over a century has passed. In retrospect, there are numerous important works that help to canonize the repertoire of the huqin. However, Liu Wenjin, He Zhanhao and Wang Jianmin remain pivotal figures that we need to remember.

Your Support

Friends of HKCO

Copyright © 2026 HKCO